“The colonist’s sector is built to last…a sector of lights and paved roads, where the trash cans constantly overflow with strange and wonderful garbage, undreamed-of leftovers…The colonist’s sector is a sated, sluggish sector, its belly is permanently full of good things.”

– Franz Fanon

“Pinball games were constrained by physical limitations, ultimately by the physical laws that govern the motion of a small metal ball. […] The objects in a video game are representations of objects. And a representation of a ball, unlike a real one, never need obey the laws of gravity unless it’s programmer wants it to.”

– Sherry Turkle, Confused Hater

“The outdoors, the beautiful environment, both in fresh and salt water. And the thing that concerns me is the amount of kids that stand on street corners, or go into pinball parlours, and call it recreation.”

– Rex Hunt, Traditional Hater

“Nobody trusts anyone, or why did they put tilt on a pinball machine.”

– Steve McQueen, Skeptic

“There is nothing so perfect as pinball and a pint at 11 a.m.”

– Tom Hodgkinson, Correct Enthusiast

“But the real thing behind the way folks feel is simply race prejudice—and I don’t say I’m blaming those that hold it. I hate those Innsmouth folks myself…”

– One of the most Hateful and Racist Writers that has Ever Lived, The Shadow Over Innsmouth (Surprise, the “shadow” is miscegenation.)

The fantastical and dream-inspiring device that would, in a few short years, truly popularize dropping a penny in a slot in exchange for a commodity was just around the corner of invention, and yet…

It was the stamp vending machine – profoundly unromantic and dreadfully functional – that became the first successful commercial device to feature a fully operational and secure coin slot. The fun, cool stuff being first past the post in this race would’ve been more elegant for narrative purposes, but it would be a god-damned lie to not give the boring, utilitarian stamp machine the flowers it has earned, along with conceding that it was the necessary final stop on a path that allowed the more captivating runner-up to flourish.

The stamp vending machine was a late-empire innovation of The Royal Mail of the United Kingdom of Britain and Northern Ireland, a postal organization with informal roots stretching back to 13th-century messenger guilds, as well as the temporary military post offices of Edward IV’s unsuccessful, but not inconsequential, 15th Century attempt to re-subjugate the Scots. It wasn’t until an edict from Henry VIII, who could see the clear military advantage of an organized messaging scheme, that the first master of the post was authorized in 1516.

The King’s Post quickly became an effective and efficient military postal system, and proved useful in a number of key campaigns, including Britain’s 1588 decimation of the great Spanish Armada, which massively shifted global sea power toward their favor. As a result, George I saw an opportunity to use the Post to expand the Crown’s smothering might, and opened up the institution for use by the general public. Developing soft power over one’s territories, after all, is a key component of successful imperialism.

It was still an expensive proposition, but the moneyed class took to it immediately. Thanks to their enthusiasm, the range and the seemingly unlimited potentiality of the Post would continue to sophisticate rapidly within, and without, the Empire’s borders. Only the English Civil War and Its aftermath brought down a period of stagnation. Cromwell saw utility in the postal system as it stood, so he merely co-opted it, where it remained laconic in the hands of his cronies in the Protectorate, but still continued nominally to exist.

After Cromwell’s diseased body deposed itself in 1598, the ruling class hierarchy of the land was restored to wealth and power, as it knew it would be (as they always know, if someone doesn’t murder all of them at once, that they will be.) The Restoration of the Crown brought a new zeal for settler colonialism, and thus for the internal oppression, displacement, and genocide that goes part and parcel with the practice.

The Throne’s desire for annexation became truly ravenous. Charles II immediately formalized the entire postal operation, officially christening it The Royal Mail, and shaping it into a focal point of the Crown’s infrastructure development. A new age of mechanization had arisen since the first George’s day, and this new technology was quickly folded into the system.

The mechanical stamp press, in particular, proved that the modern efficiency of machines were favorable to the bottom line, simply by more quickly doing the same dreary tasks. In this “Luddite’s nightmare”, the job of stamping didn’t itself get less dreary, but the mechanization removed people from the natural processes of society, and made their lives even less valuable in a hellscape of technological capital that ultimately did not care if they lived or died.

The Royal Mail quickly spread across the Empire, feeding its own growth as it aided in expanding the Crown, proving as useful to the Empire’s business interests as Its lust for territorial domination, which, ultimately, were one and the same. No amount of the Crown’s treasure would be spared in assuring the dominance of the Empire’s communication lines, as they were seen as essential in the on-going colonial project.

All of that money had to come from somewhere. The Royal Mail would surely never admit the lengths to which it was indebted to, and also helped perpetuate, the specific industry Britain would make its first enormous profit in. But it most assuredly was, like every other major institution and expansive operation undertaken by the Crown in its final march to world domination, totally supplicant to Britain’s single most prosperous and monstrous economic enterprise in the whole of Its history: The transatlantic slave trade.

Listen… this place is a breeze for me to hang out in. I blow hours in here, all fuckin’ day sometimes when I’m fiending strong. I’m always fine so long as I’m masking my presence to the level of an anonymous white guy (which indeed, oh boy, is one of the things I very much am.)

I can be one of the hundreds of generic white dudes, as long as I’m alone. I’m never bothered, always ignored outside of those rare moments I choose not to be. Alone, I am invisible in the Logic Gate, a proper and expected part of the background scenery.

So it always pisses me off so profoundly that my experience is materially different when I’m here with a more diverse group of folks. Even if that difference is usually “just” a mild shift in vibe, my brain-shit can’t help but pick up on the mood as we, a foreign entity, engender constant mere disdain.

I’m not saying my empathy is perfect, but it’s pretty easy for me to read the faces and bodies of the other anonymous white men in the Logic Gate, when they’re even lightly exposed to people who look, sound and generally behave in any way differently than they do. And since I hang out with a bunch of take-no-shit weirdos, things here can often go from “vaguely tense” to “a whole fucking thing” with the quickness.

I’m guessing today will almost certainly not disappoint that arena, given Picky’s reputation here as an uppity queer with no respect for patriarchal hierarchy or indeed, authority at all. She’s almost always kicked out for one reason or another, and has received three different lifetime bans, one at the business end of a shotgun. But she always somehow ends up back here with little trouble until the next trouble she causes.

To be very real, although I’ll always defend my pals, coming here with Picky is not one of my favorite things, and my anxiety in being here with her is only contained by the inherent joy of being around a bunch of pinball. For her part, she seems to delight in accompanying me here to inflict her adventures on me. She’s just lucky we share similar addictions; I trust her Pull is real, but she sure does a lot more inflammatory shit talking than pinball playing when she comes.

As for the current adventure being inflicted upon me, Picky’s desire to come through that backest-of-backdoors, into one of the more abandoned sections of the Gate, suggests to me that she may be on someone’s specific shit list. But her casual treatment of the camera doesn’t add up if she’s hoping to avoid that trouble for long.

Yet it was her Hans Gruber bit that probably over-exposed her true intentions (as her dedication to bits, being her downfall, often does.) That specific line, as every neurodiverse fan of Die Hard knows, indicates that part of Hans’ plan was purposefully alerting the Feds in a seemingly foolish way. And no matter what, the likelihood of trouble finding us will increase on an exponentially curved line the longer we’re here. This rathole is full of fucking narcs looking to score points with the Junta.

As for the “real” law… the pigs are always well represented this close to the Carnival’s sucking, spewing mouth. It’s a money-flush, fast-and-loose area, with a shit ton of tokens, tickets and other chits flowing through the ten cubic kilometers surrounding us. A cop’s primary job on the Drop, after all, is to see that the Tokenflow isn’t fucked with by unsavory, non-corporate elements, lest the wrath of Mammon befall them (this wrath being functionally carried out by the cops themselves, of course.)

The fact that the Inner Skirts are more than a little sleazy also helps Johnny Law accomplish their secondary mission; to shake down every token and ticket they can scrape, grift, and steal from these good-time mean streets. This area, with all of the drugs and humans trafficking through it, is an enticing prospect for any vice cop worth their crooked salt. Thus the operators that work these cubes are some of the least trustworthy, most dangerous pigs on the Drop.

No cops seen at the moment, unless they’ve recently upped their barely incognito plain-clothes game, as we pass through narrow, dark hallways, featuring mostly-abandoned rows of pristine and beautiful older games – god I wanna play them – before we take a quick left into a nearly hidden side door, only about a half-meter wide, tucked between a Pool Hall Hustler and a particularly lovely example of Skyscraper – complete with a working Elevator door that pops open occasionally, with some cheeky art of a man and probably his secretary caught in a moment of embrace – they’re looking at the player with wide, surprised eyes, as it dawns on them that we’re notorious gossips, and news of their little tryst will spread through the office like wildfire – and we squeeze ourselves out into a more populated, and thus cramped, space.

We’re definitely still well deep within the bowels of the Gate, but this hallway, despite its superior lighting, decoration, and buzz of human presence, always gives me that uneasy sensation of being in the wrong neighborhood. This place feels to me like a grinning wolf trying to lure you off the path, with a truly shifty vibe that threatens to grow dark at a moment’s notice. But you know me… I’m very risk-averse.

We’re in what’s known as the “Rock Room,” and maybe that gives you a hint as to why it’s not one of my favorite places. I mean, of course it isn’t that I don’t like some truly awful bands, and some pretty good ones, many of which are featured, in pinball form, in this very hallway. If it was empty or sparsely populated, I would probably spend a lot of time down here, and would have a warmer feeling toward it, especially situated so deep in the Gate, so close to my darling classics.

Unfortunately, this hallway is usually fairly crowded, and in this case the “out-of-the-way area” is a feature for the particular cadre that inhabits it, not a bug. In the most basic parlance, the Rock Room is a kind of backwoods clubhouse, adorned with the customary neon booze signs and other tat that skews male-interest. It’s for cool dudes of a certain age, who want their very own special place where they can mostly behave how they like.

A couple decades ago, niche entertainment companies realized that the most fiscally prudent way forward was to focus on providing products to middle-class white guys, who could be counted on to drop big bucks on expensive toys, in their desperate efforts to fill their growing heart voids with the poison treacle of nostalgia. For the few remaining conglomerates that have survived the many hells of economic samsara, it is now practically the sole focus of their business models.

But before it all became pandering nostalgia-bait, it was alive within the moment that inspired that nostalgia – an era of scummy potential and lead poisoning, when the world of pinball seemed to exist in the shadows of society, considered a pastime for bad teens and degenerate gamblers who wasted their precious earning years in the dive bars and pool halls of America.

This whole situation is mostly a myth (not the lead poisoning – that shit was crazy – but the evils of pinball,) an upper class understanding of a fun thing that crosses paths with elements the wealthy would always claim to find unsavory, even if they themselves indulged in that very “vice” behind the closed doors of their bourgeois homes. It was a bigoted idea about the kind of person who enjoyed pinball – the silver ball’s reputation at the time was not unlike another “passing fad” that the General Public of the day found unseemly: rock-and-roll music.

It was in those reeking pinball rooms (the thick plumes of cigar and cigarette smoke and the carpet of ash were no myth, at least) of the late sixties that the connection between pinball and Rock began in earnest, in days where trademark and copyright law had become almost as hazy as those pin-filled chambers.

Soon enough, the law would be updated to give the corporations total control over the properties they bought and owned, and every aspect of both pinball and music would be fully commodified. But the decades prior offered a wealth of creative freedom as well as shameless duplication.

The first Rock pin came along in the era where mass-market entertainment for teenagers transitioned from a boutique concern into a major global industry. Copyright and trademark law were actually already long in the tooth in America, being a major portion of contract law since it developed in the 18the century. But when the mass media revolution exploded in the early 20th century, it would take decades for those laws to catch up fully with corpo modernity, until the Copyright Act of1976 set the stage for full corporate control over things other people came up with.

Those decades of murky legal miasma created an era for opportunists to strike. One such company, which had never been shy about the ways of expediency, was Hewer. Hewer was one of those old Windy City pinball companies already comfortably ensconced down on Chicago Street, (not ours, the one in Reality… although its name came from ours, complicatedly,) right next door to eternal enemy and future partner Bobsidy, and within the same five city blocks of both the Finster brother’s tiny outfit and the current market leader, Angel & Sons.

Hewer had made its bones by prudently chasing trends since its founding in ‘46, back in those wild times where a trend might last for more than a season. For its first decade, Hewer’s pins were generic, mostly slightly different versions of whatever Bobsidy was doing. But as the Sixties dawned, so did a new strategy: they would piggyback onto popular culture rather than the guys next door.

Two such projects had become extremely successful for Hewer, both based on popular television properties, with just enough elements changed to keep things nice and vaguely legal. This was a common tactic for pinball companies of the era, but no one flew as close to the sun as Hewer did.

Silly Sheriffs was a colorful and obvious take off of the Andy Griffith Show, produced in 1963, featuring two of the wildest ersatz caricatures in all of ‘60s pinball backglasses. It was an unholy blending of Griffith’s and Knotts’ most prominent features, made grotesque and switched between the two gigantic, bulbous heads, which were tightly squeezed out of the windows of their out-of-control cop beater.

They’re both grinning like idiots, shooting off rounds into the air like cowboys or bangers on the 4th of July (ersatz Barney has about eight too many bullets, sadly – no respect for the canon,) as they careen toward the “BRIDGE OUT” sign and the lake beyond it, while a little red-haired boy who’s fishing on the shore looks on in something between hilarity and horror.

Even more successful was Wrongly Accused!, an attractive 1965 pin featuring a colorfully dark backglass with the focus on a man, early 60s-handsome, clad in a trenchcoat and looking conspicuously unlike David Jannsen. The fellow is hunched behind a brick wall, his roguishly roughed-up face set in full gritted-teeth mode, as his bloody hand dramatically grips the end of the wall. Around the corner and down the alley, there’s a cop car with open doors, and the silhouetted forms of two policemen running towards our hero, their guns outstretched in front of them.

Now, these silhouettes could be interpreted as if both of these men’s non-gun hands were hidden in shadow, but it also looks very much like both of the cops are missing an arm.

(There was also a popular rumor that the silhouettes of the cops’ faces lined up neatly with the Silly Sherriffs, but it was the one-arm thing that brought the heat down.)

This was the last game ripped off from American media that Hewer made, as they faced significant pushback from United Artists. UA sought to set legal precedent. since they were making a considerable little bundle off of licensing out a popular weekly-watch program like The Fugitive, and the consequences of unlicensed merchandise were starting to show up in the numbers. Hewer’s Lawyers, one of the finest firms in Chicago, managed to contain the case into a “we realize we were bad, and promise we won’t do it ever again” scenario, just scraping past the short sharp teeth of the blossoming law.

And they didn’t do it again… for a while, but then along came a few lean years, with lower sales annually and accompanying steady profit loss. None of their newer tables were catching on, and the narrative quickly went reactionary. Instead of Hewer’s failures being of Its own creation, it was the law’s slap on the wrist that was feasting on Its bottom line.

It started to sound to the boys down on Chicago Street, arch libertarians to a man whether they knew it or not, that some sort of corporate communism was going on. The American Way was to find a path to the money, slipping through both law and taste in order to hit the craven heart of American joy. The big-money Hollywood Attorneys could eat shit. The whole of Hewer had decided, unconsciously and unanimously, that this would be the way.

The idea boiled up that maybe reaching outside the hateful eyes of the American Film and Television Industry was the answer to their woes. The power of groupthink solidified this vector, and when their well-paid lawyers responded with an “eh, maybe?” hand-tilt, it became the foundation on which the designers could dream in earnest, as their creeping desires returned to those already-flowing wells of cash from which they had previously embezzled.

Hewer focused on the murkier world of overseas properties, and to put another layer of denial in doing what they were clearly not supposed to do, they dipped into an even scummier and grimmer world than Hollywood; the international music industry. Specifically, the one that had made a deep dive into the young American psyche. It should be no surprise, really, that the first pinball based on a band featured an ersatz version of the Beatles.

Meet the Beebles, released in 1968, features a backglass that offers the scene of a band of four anthropomorphized Bees, each with heads topped by a thick mop of satirical mod hair (a style that the Beatles, already nearly broken up, had long abandoned, giving Hewer even more self-delusion to think this would all be fine.) The bees dance and spin through the air, according to their motion lines. Three of them have caricatured electric guitars, while one plays on a little snare drum harnessed around its shoulders.

The bees are all crooning, closed-eyes and rising brows, lips comically pursed, fluttering around a cartoon representation of what is certainly supposed to be Elizabeth Tower. Big Ben itself has been replaced with a giant beehive, which has also been given the vague impression of a vinyl record. This fun gimmick will occasionally spin around when a few different combo shots are completed, and during the bonus total at the end of a ball.

Likely, the most comically ironic detail about the machine is its lack of rock music of any kind. This was still the era of ringing and knocking being the closest thing to a game soundtrack, and the machine’s EM circuitry was only advanced enough to play a dozen or so notes at a time.

The game did at least attempt a slightly-changed version of The Yellow Submarine that played at the end of the ball, and although it didn’t sound terribly close to the original, it was probably the detail that pushed the things fully over the line.

Or so I’ve read. Even though I’d love the chance to play it, or even just look at it, I’ve never seen one. I don’t even know what the hell the playfield looks like.

There are a couple of reasons for this; the first being that Capitol Records did notice (of course they did, they’d been maximally enforcing Beatles-related Copyright and Trademark torts in America for almost a decade, and they were absolutely the worst band Hewer could have chosen. Those best-in-city lawyers were all very fired.)

Capitol were, of course, very much an American company, with prime access to the American courts and a set of case law they’d helped build, meaning they could fully test that “pinky swear” scolding Hewer had been given for its last infraction. This time, the cold justice of American capital was swift and final, and Hewer was sanctioned by writ of injunction from ever releasing the game.

Hewer’s factory floor had been in the process of ramping up production, as the first fifty machines they’d produced had sold quickly, and they were convinced they had a hit on their hands. They had a stock of 300 units, nearly all pre-sold to distributors, by the time the legal hammer came clamoring down.

All of this stock was ordered to be destroyed, and although a number of them did surreptitiously escape the grinder, they were quickly absorbed into private collections. There are likely less than 100 of these machines in any state of working order in either Reality or real life.

(One of the Maker’s more annoying quirks is the way it follows scarcity patterns in Reality in its production tendencies, even though it could easily make as many of a thing as it wanted. It’s the Maker, after all, and the Maker ain’t no commie. Likewise, no one who’s been granted use of a private prodbox is going to mass produce an item of rarity, as that’d be counter to why they were entrusted with one in the first place.)

The second reason I’ve never seen this game in the real world is the one I take much more personally, and is materially connected to the way the Maker encourages all of this scarcity. There is, apparently, a mysterious motherlode of rare and special pins that the Junta have stockpiled in some locked-away storage room deep within the Logic Gate, which they refer to as the “Special Stash” (the junta have a knack for coming up with names for things that are simultaneously corny as fuck and yet somehow still too cool for them.)

The kicker, of course, is that this “stash” is only accessible to the Junta, their close mates, and any VIPs they might want to try and impress. Not only is this kind of in-group behavior total bullshit, as games are meant to be played by everyone who would like to play them, but it also proves decisively, for me, that the Logic Gate is not what it pretends to be.

Anyway, there were a few more Rock pins – mainly based on the teenage sock rock of a bygone era – in the ensuing years, as both the pinball industry and greater society yearned more for the nostalgia of the 50s than the very scary modern moment. ‘72s Soda Pop Hop is the most popular example of this phenomenon.

Companies, well spooked by the fallout from the Hewer case, stayed away from direct references to any real band of any generation (although there were several games that did feature slightly mutated versions of the Fonz.) As a result, the treachly Rock pins of the first half of the 70’s ended up as mere curiosities, in genre terms.

The most significant Rock pin, historically, came in 1975, due to the explosion of rock’n’roll as a business concern, to the point that marketing departments started to call concept albums “rock operas” and advertised the living shit out of them. When Bobsidy produced The Who’s Quadrophenia, it was a big deal, and a true watershed moment for the future of pinball.

The game was expertly crafted by Avic Ziemianin, Bobsidy’s design master at the time. Ziemianin was often accused of having a repetitive design style, but his tables nevertheless usually ended up both fun to play and easy to understand. This game, in particular, featured his well-developed gameplay flow, and it was highly colorful, showing off the band and their aesthetic with mid-70’s psychedelic aplomb, even including several subtle references to Tommy, which was released at the tail end of it’s design.

The Who’s Quadrophenia was a sensation in the pinball world, selling the most units in the history of pinball. It changed the landscape and trajectory of the industry overnight, by proving that spending the capital to obtain actual licenses could return massive dividends.

Once Quadrophenia took off, the Rock pin genre quickly established itself as the hot new thing in pinball. New games quickly followed, featuring artists such as Rod Stewart, The Steve Altman Band, Styx, and, of course, Cher, the “First Lady of Pinball.”

This era of Rock pins is cursed to be the last era of pinball with electromagnetic technology. In effect, they had beaten the pinball machine’s ability to actually play any rock music to the market by almost half a decade. The Rock pins of the late 70s were all still EMs, with simple hard coding via binary switch configuration, basically an analog assembly language.

The guts of an EM are a sight to behold: bundles of hundreds of wires looping through long rows of logic-gating transistors, a recursive procession of messy-yet pattern-forming analog tech that invokes Yeat’s fearful symmetry and, even to these cynical eyes, Clark’s thesis about sufficiently advanced technology and magic. (You could even throw in the last five minutes of Koyanisqatsi if you like.)

The fact that these innards interact in a way that turns a simple binary analog codebase into a robust and sophisticated gamestate is both an engineering and natural marvel, and that it all works in perfect conjunction with the joy of manipulating gravity, well… the electromagnetic pinball machine is a true miracle of the state of materialism.

But when it came to the soundtrack, there was nothing about the EM that seemed ahead of its time. Since their invention in the 30s, the “music” of electromagnetics had stayed essentially the same; a collection of basic rings and knocks. It was a paradoxical situation that gave all these Rock pins of the late 70s a dissonance in tone that would quickly feedback into novelty-killing ambivalence.

Solid-state pinball – that is, a pinball machine that runs on a boring digital microprocessor instead of wonderful looping twisting spiralling wires – had been prototyped as early as ‘74. But it would be a long five years to bring it to the market in a cost-effective manner, as the new format required a different set of skills to build and maintain, not to mention that the factory floors would have to be completely reworked for the digital age.

So The Who’s Quadrophenia, and the next fifteen or sixteen pins based on rock bands, didn’t actually rock beyond a player’s predilection for challenging the tilt gods via nudging and slapping the machine. There was nothing resembling music except for the old playfield percussion, who’s charm had worn out its welcome after four decades and change. As the digital revolution began to crest in an American Empire that was just past its own cresting moment (and was now staring down the steep mountain drop of imperial collapse.) people seeking distraction were beginning to expect more non-literal bells and whistles from their professional-grade entertainments.

Still, many of these Rock pins were extremely successful in their time, especially the earlier titles and ones built on personalities who would strongly endure through the eighties (The Gambler featuring Kenny Rogers is the best example of this.) They are, by the nature of the Rock pin genre’s rise and the pinball economics of the time, the most-produced Rock pins in history.

Thanks to this, these tables have been reproduced by the Maker by the thousands, to the point that there are way too many of them to be profitable to anyone. Many of these tables come totally busted, and an oddly high percentage of them come out Tricky, and are immediately confiscated by the “proper authorities.” Still, there are so many normies that they often show up as filler tables in the Rock Room, and even outside of it.

Here in the Rock Room, you’ll often see a few of the same older machines next to each other, sometimes almost directly across two other twin copies. Tables in all parts of the Logic Gate are constantly moved and shuffled and brought in and taken away, and these plentiful, low value machines, which could be practically donated to someone who really wanted one, have become standard filler material, apparently in an attempt at visual and spatial continuity, to maintain an illusion of fullness. Those of us who spend a lot of time here can’t help but constantly notice the sense of discordance in the Logic Gate’s mise-en-scène.

So why are machines always being carted off, just as I’m getting used to them, and why do favorites have to be traded out for one another in this enormous space that could fit them all? Why are there barely any rare or prototype games on the floor? And what’s with the desperate need to make the place seem full, but only to those who aren’t paying enough attention to see the constant repetition? Who are the Junta so desperate to impress?

Despite the Logic Gate’s portrayal as a “museum,” as a repository for pinball history, this behavior doesn’t add up. There are too many holes in the carny simulation the Junta is trying to run here…

Aaanyway, It was just as well, then, that the solid-state revolution came when it did, as the novelty of EM Rock pins was wearing thin. The gimmick of being able to hear the band’s actual music while playing the band’s actual game proved to be a strong one. Hearing one’s favorite riffs in all of their tinny, synthesized glory, as well as the short vocal callouts which felt pretty revolutionary in the moment, were great for all of pinball, and specifically for the Rock pin.

(And for the Rock pin, there was some irony of the acceptance of synthesized music among the fans who repped both rock and pinball, considering that, at the same time this digital pinball revolution was occurring, white male rock culture was violently rejecting the fully synthesized queer disco revolution they feared was coming, going so far as to having a Nazi culture-burning rally at Comiskey Park in 1979, that amounted to a symbolic pogrom against all who threatened white men and their barely-contained rage.)

The first Rock pin to actually ROCK, although one’s conception of how much this Rock pin rocked is tied to just a shit ton of external factors beyond the synthesized music, was 1979’s Alice Cooper’s Insides, by Hewer, who had turned themselves around into a legitimate concern, simply by following the path of their hated next-door rivals, and buying people’s ideas rather than stealing them.

It was, as many early format games tend to be, all around lousy, with lethargic gameplay and a poor understanding of the new technology it introduced. In this case, this table, which clearly fronted an air of excitement and speed, focused way too much on elements that slowed gameplay down, like orbit lanes your ball seemed designed to float through rather than slalom. All of the ramps had little loops at the end that stole the ball’s kinetic power, so that it plunked down lazily rather than snapped excitedly onto the upper playfield, who’s simple buffet of drop targets seemed to harken back to another era. It was a game where the meta should always be f l o w, and yet it constantly grinds to a halt.

Ramps and loops weren’t new, but they were new to the game’s designer… Avic Ziemianin, who had left Bobsidy (now known as just Bobsy since everyone who understood the original pun was dead,) the first company to really embrace Solid State with gusto. He was getting on and didn’t have much interest in the new fad, so he decided he would spend his remaining working days next door, where he was warmly welcomed. The higher-ups at Hewer assured him that their EM production would remain steady alongside the whole solid-state brouhaha.

After he made the move, Ziemianin felt a new sense of revitalization, and, as is an old fool with money’s wont, he soon found himself with a new, much too young bride and child. So when Hewer announced it would be going 100% solid state less than two years after they’d promised him they wouldn’t, the company only had empty apologies for Ziemianin, who now found the idea of retirement financially ruinous. So he did the only thing he could, and tried to adapt to a new world that had likely, even from his perspective, left him more than a bit behind.

The finished project proved his fearful suspicions; the game was a stinker, and everyone at Hewer knew it, including Ziemianin. It’d be hard to find a sin as great as anemic gameplay for a hot new title with hot new tech, but Ziemianin had managed it, and by the time he realized his mistake, the production date had arrived. The game would ship as it was, and his reputation for impeccable sound design would soon be in tatters.

Ziemianin had always been proud of his sound design, and considered doing it himself an important part of his overall table feel. Others agreed that he had a knack for it, and his work became unimpeachable through successful repetition. He was a master at his craft, but he was utterly, foolishly unprepared for the differences between the aural needs of an electromagnetic and a solid-state machine.

EM sound design worked by being busy, by keeping the noise lively and creating a series of repetitions that created the impression of a dynamic soundscape with a limited toolset. Solid-State, being digital, could do pretty much what it wanted, even within some pretty tight memory limitations in its early years. Ziemianin brought his EM philosophy to a Solid State playground, and ended up in a valley most uncanny.

He chose a limited sample palette, preferring to put most of the memory toward the soundscape, which wasn’t yet capable of fully rocking whole songs, but could create more than the vague impression of crunching riffs. It wasn’t a bad soundtrack, although it was underwhelming from what had been originally expected. But it was the samples that truly sucked the mud on this one.

It was one particular callout that truly aggrieved, of the five apparently available (I think I heard another callout one time, but I really do not care for the game, and thus rarely play it.) The offending sample was Cooper simply going “YEAOW!” which, on its own, was merely slightly obnoxious.

But it was triggered by hitting the bumpers, the drop targets, and the loops; basically anywhere you shot no matter where you were aiming would give you that same fucking “YEAOW!” over and over, sometimes rolling over one another as if the machine was trying to scratch a record. Anyone playing this game for more than fifteen minutes in a day would inevitably hear that goddamn “YEAOW!” in their goddamn sleep.

So it was a lousy game based on a two-year old album that had already solidified Cooper and his iteration of “shock rock” as passe. Trust pinball fans, always suckers for novelty, not to concern themselves too dearly with matters of taste: the game moved a literal shit ton of units, more than any pin in the previous three years. The lousy sound design became a meme of the day, treated more as absurd than aggressive. Alice Cooper’s Insides cemented the solid-state machine’s future as ubiquitous, while also establishing the general aesthetic of dark, teen-age moodiness as the future of Rock pin design.

Gone were the wild colors and abstract dynamism of the ELO and ABBA games of just two years prior. Gone was any hint of the waning aesthetic of the late 60s that the boomers had clung onto for so long. This was the time of jet black and blood red, of backglass flames and summoned demons. Honestly, not a bad look in a vacuum, but when it’s every third game released, it gets old fast.

(Ziemianin would be more-or-less forced into retirement by an unsatisfied leadership after finishing this game, despite its surprising success. In his heart he already knew he was done with pinball, and with work in general. Thanks to a fairly generous severance as reward for his bad game doing good, his remaining five years of life were lean but pleasant: he saw a bit of the world, died in his sleep, and his wife and child found a suitably-aged replacement without much fuss. All in all, he had as happy an ending as any of us could hope for.

Whenever he was asked about the experience and subsequent “choice” to retire, Ziemianin would always say that he didn’t love the new hardware, but the thing that had truly put him over the edge was the semi-regular rambling telephone calls he was required to take from Cooper, whom he called “an unwell, unpleasant man.”)

As the decade turned, the reinvigorated genre got hot again, buoyed by the solid-state novelty of rock sounds and callouts. But as the 1980s progressed, the year after year decline of the Rock pin returned, and it didn’t help that pinball had managed to get itself caught up in another moral panic, as Middle America decided that satanic cults were real, and that they had their symbols and signs everywhere in the culture. Pinball tables, many of them covered with pretty explicit occult imagery, started to disappear fast, especially from the South.

Beyond the evangelicals having their fun with their games of toxic mysticism, it was becoming clear that pinball chasing the Rock genre was reaping diminishing returns. The marketing of music had purposefully ghettoized genres into their own individualized “long, plastic hallways,” where the industry’s thieves and pimps could have the freest reign, hidden within their own shallow money trenches. And an essential part of music marketing was antagonizing genres against each other, mostly according to race and class, in order to create the most stable revenue streams. The pinball industry itself was growing too quickly to remain catering to specific, contained markets like rock bands.

It was the tepid response to the release of Def Leppard’s Pyromania Pinball in ‘86 (kind of an under-appreciated classic due to its status as a nadir, tbh) that spelled things out in a brutally honest way: the Rock pin was becoming a millstone around the neck of the pinball Industry, which was now in the process of being fully swallowed by the greater corporate machine. The corporations’ rabid focus on cross-branding was providing the industry with more access to mainstream entertainment properties, and pinball itself was proving useful to the corpos for horizontal promotion opportunities.

The Rock pin faded at the worst time for fans of the genre, as 1987 would see updates to the solid-state platform that would feature Dolby sound and fully digitized music. Instead, it was the smothering age of the Mass-Market Licensed Property Pin that reaped those fruits, while featuring licensed games with an appeal much wider than any one band could provide.

Most of these games were either tie-ins to already-beloved properties or based on movies expected to be massive hits, such as GI Joe and Commando, (they didn’t always get this right, which is why a Ladyhawke pin exists.) Pinball was entering its silver age, and its most profitable moment, and the Rock pin would not be a part of it.

Movie and TV pins, of course, were not a new thing, but the vast majority of them up until the 80s were thinly veiled “parodies” of sci fi properties, like Battle Sun, and Millionaire Cyborg. Rambo: First Blood was the first movie pin to sell a massive amount, but in a curious twist fate, the actual first pinball game based on a movie was The Who’s Quadrophenia, giving it the distinction of being the first Rock pin and Movie pin, ( although some might put an asterisk on that one in the record book, it being essentially the same game.).

In 1982, Bobsy decided it would be cost efficient and a bit of fun to adapt the existing Quadrophenia EM into a solid-state machine in the wake of the movie, which had been released four years after the album. The movie was a dour, moody tone piece, and featured precisely no songs by The Who. So the overlay design met the movie halfway, and blended black and white film images in between tableaus featuring in the original album’s manic palette. The soundscape had some nice, crunchy sounds that were the best representation of music yet, and the callouts were from the movie, although all of them are hilariously difficult to parse as human language.

It looks like an interesting machine, but the sales were poor since the gameplay itself now felt ancient, especially to newer players, (sorry, Mr. Ziemianin.) The solid-state nature of the machine didn’t change the old game’s scoring or layout, merely its overlay. People expected ramps by now, and modes, and all of the other tech that had been piled onto the playfield in the fast-moving last few years. It was simply too early for a throwback novelty such as this.

A legal snafu popped up a few months into production, where it turned out there were rights issues between the band and the label that technically made their game’s existence illegal, in a coincidental parallel to Hewer’s problems a decade earlier. Quietly stopping production on a game that had been made for a giggle seemed the more financially prudent move than sinking money into a losing court case for a project that was never going to turn a profit anyway.

I would guess that there are less than 40 of this rare version of the table on the Drop. The original 1975 EM is present in this hallway, of course; in fact there are always at least two of them, one at the front for the squares and olds and one at the back for the cool guys. And as one of the more produced pinball machines of the 1970s, it’s use as a space filler is ubiquitous; you’ll often see both this machine and the Alice Cooper pin used out in the GP wild, often in odd juxtapositions, simply because there are just so gosh darned many of them.

As for the updated, super-rare version… just like Meet the Beebles, I’ve never seen it. But like that game, one of these does apparently exist here, in the Logic Gate’s Special Stash (Christ), according to rumors that persist so strongly that they sound more like a brag.

I’ll never see either of these machines, although I kinda desperately want to. To gain “legal” access to them I’d have to properly bootlick anyone connected to the fascist pigs who run this place, and I’d much rather die. To be honest, I’m so guileless (or at least seem to be to myself) that I’d never be able to fake shit like that, unless maybe I got a rail spike through the ol’ cranium. Anyway, none of that matters because I’m already well-associated with the enemy around here.

Picky talks big about someday breaking into the “locked room,” as she calls it, but even she understands how nuclear the Junta would go on her if we got spotted – like, real guns-blazing shit. The back hallways of the Logic Gate are said to be convoluted, and I have no problem believing that this pack of fucking knuckleheads have installed the kinds of death traps they often like to dream up live on stream. Death-trap obsessed, this lot.

(A thought suddenly solidifies… am I about to get permabanned from this place due to previous and approaching hijinx? Or, Is this willfully dangerous nonsense actually part of today’s plan, to throw ourselves into the gnarly “Wrong Turn” world these urban hillbillies have set up for outsiders in the back halls of their plywood-paneled hell?

I dismiss the “dying” part, as I trust Picky has respect for the potential violence these freaks are capable of, and why it’s always the sort of damage in a system that you want to try and root around, at all cost.

Then again, we’re talking about Picky here…)

Neither of these missing-but-not games will ever be put out here in the GP area, never will the Junta give almost anyone outside of their inner circle a chance to play, or even look at them. Nevermind all the poor sods who have so many specific fiendings tied up in a collection of rares they’re denied access to. The Junta ignores their pain, but never misses an opportunity to crow about all the good stuff they might have tucked away, just for themselves, their friends, and their “VIP guests”.

This is because the Logic Gate isn’t simply a “collection”, and it isn’t a “museum” at all. Like most of the “museums” on the Drop and in Reality which display a massive collection of the same sort of thing, (again, think of every car museum run by some rich guy with too many cars) the Logic Gate is nothing more than a goddamned sales floor.

It’s this barely concealed fact that determines what games us proles have access to in GP, and it is the kind of profound carny horseshit that makes me wish for this entire junk heap to snap off of its chord and get swallowed forever by the sinister pit below.

The “Special Stash” (Jesus Christ) is not a clubhouse, but is, in fact, an exclusive premium sales floor for very rich men who want buy the kinds of pinball machines that make them feel very rich, and allow them to casually say things like “you know, this is the only one in the whole world” even though there are, like, 20 of them, in other asshole’s collections, who all claim their own units as singular.

There’s no love for pinball in that room, only for aesthetics and money, which makes it a Holy Space of Individualist Virtue, according to the one true religion on the Drop.

And everything out in GP is similarly for sale, which is the whole point of its phony abundance. You just have to be willing to vastly overpay for it – since the Junta owns the majority of the pinball tables outside of the Carnival, it gets to set its own prices.

Fuck, I hate this place. Fuck, I love pinball.

Fuck.

The only way to truly sugarcoat Britain’s enthusiastic participation in the institution of slavery would be to get a roomful of esteemed British economists and historians to discuss the subject. While you’ll always find the supposed experts of an ongoing concern like a nation-state downplaying the negative aspects of the institution that has given them prominence, the topic of slavery is treated in a particularly nasty way among the Tory-sympathizing academia of England’s hallowed halls of learning (Both of them.)

According to the Official Record, any slavery on the isles of the future United Kingdom itself is the fault of the Romans, who introduced their favorite institution after their invasion in the first century. In actuality, the Romans simply formalized a practice they had already found in the full of its blossom, everywhere in Europe they’d colonized. It was no surprise to them to find that a backwater hinterland like the British isles had, in its isolation, advanced the technology of human bondage to an already sophisticated level, nor that it was subsumed very easily by their own.

After the Romans abandoned the Isles in the 5th century, as the totality of the Empire’s focus turned to the chaos at their inner core, the Anglo-Saxons swept in and easily conquered the already-decimated peoples of Brittania. And when they took power, they were happy to continue the vicious business practice of the previous freeholders. Chattel slavery increased under the Saxons, particularly due to border skirmishes and subsequent kidnappings of the Irish, Scottish, and Welsh, who represented the vast majority of slaves on the main island.

It is the Normans, in their massive invasion and subsequent swift and brutal crushing of the Anglo-Saxons in the 11th century, who are particularly credited with ending chattel slavery as a concern on the Isles, although if you hear someone telling this old chestnut and they stop there, ask them to please go on.

The Normans were a clever lot, and they brought the sophisticated and parasitic technology of serfdom with them to the Isles. It had been working well as a state system on the Continent, and when this collective apparatus clashed with the more individualistic view of slaveholding among the Britons, the former quickly proved the latter as the needless vestigial organ of a lower-tech peoples who’ve been dominated by a superior culture.

And so, the thing British Historians often call “the official end of chattel slavery In Britain” was totally subsumed under a newer, more profound slavery, by another name. The everyday horrors of a slave’s life continued unabated – trafficking, sexual assault, summary execution, overwork and starvation, abandonment when “necessary”, and wholesale slaughter on rare occasions of the pox – now all neatly packaged into one massive “lower class.”.

While this arrangement was undeniably brutal, it was still a relatively self-contained structure of white supremacy, as the slavery and serfdom in Britain primarily consisted of peoples from the British Isles themselves. Serfdom was mostly a white-on-white system of power and violence – further proof that, in a vacuum, the white soul’s need for social tension and domination will lead it to be bigoted against itself.

For instance, the third generation of Norman royalty invented and popularized the idea of calling oneself an Anglo-Norman, identifying with the whiteness of the previous royalty in order to further demarcate the distance between the dirt-white blood of the serfs and the rich, pure anglo blood of they supposedly possessed. It’s always the third generation, isn’t it?

But of course, racism and bigotry were far from merely a white person’s concern on the Isles. There had been black folk in Britain consistently since the Romans had brought them in bondage in the first century. While most returned with the Legions when they were called back to Rome, many escaped, were freed, were killed, were captured, were sold…

A few got lucky in the intervening years, earning places of high esteem and forming small communities of their own. Most had no access to anything as ephemeral as ”luck”, living subjugated lives under the white boot. But they all carried an extra burden of suffering, for being so easily labeled as an outsider by the white mind via simple sight.

The stories of these people are a unique and important part of the full narrative of the British Empire’s relationship with black slavery, and those smaller narratives are not diminished by the horror that their collective experience presumed. Their treatment was a refraction of the future, of the true hideousness of Britain’s involvement in the most cruel and vicious acts of slavery to ever be perpetuated upon humanity.

The Rock pin died for much of the late eighties and nineties, while the pinball industry itself reached its heady and deceptive zenith. With the 1991 introduction of dot matrix displays, which produced crude images that could be cleverly manipulated and stylized by talented designers, pinball was finally able to claw back some of the parity lost to video games.

Video games had been eating more and more of pinball’s lunch over the course of the ‘80s much of it spurred by the furious technological arms race between companies in Japan. Although the Japanese arcades were facing their own challenges and decline, they still made real money. The need to stay ahead of the competition and stave off a near-future collapse forced the rapid innovation of Japanese video games in both design and tech, until video gaming was, as the nineties began in earnest, several orders of magnitude ahead of pinball in the arcade space.

The early dot matrix days were the true salad days for the industry, as the growth of the pinball market exploded into its own exponential period. The innovations came fast and furious: more modes, crazier multiballs, extra flippers, and plenty of easter eggs – all the newer, higher tech toys and contraptions. There were tricks and traps and interactive toys, many of these tables were bursting with the delight of pure creative freedom, and a few are definitely some of my favorite pins of all time (Jolly Jesting Jousters and The Outer Limits Pinball immediately come to mind.)

But with these new gimmicks came rapidly rising production costs, as the price of an individual machine nearly tripled over the course of a decade, and kept hedging upwards. Pinball had, by earning record profits, somewhat accidentally put itself in an extremely precarious spot.

Ultimately, there was nothing in particular that anyone could have done to stop progression into a doomed future. In the mid ‘90s, the video game market began shifting rapidly to the home, as the newer consoles were beginning to approach technological parity with dedicated arcade machines. The subsequent strangling of “third spaces” like arcades in the United States signaled the end of pinball’s 80-year streak as a profitable business concern.

No amount of dive bars and pizza joints were going to be able to afford these expensive new tables at any cost-effective scale, and the home market for pinball had yet to blossom. Being a part of the mega-corporate machine had some great benefits, but the key drawback was how quickly your specialty could become extraneous in the eyes of the money.

Arcades, as the kids of the 70s, 80s, and 90s had known them, died a sad slow death in the shadow of the writhing millennium… and then pinball died, done dirty by the mega-corps’ need for lines that forever trended upwards. By 1999, after having merged in the mid-eighties, BobsyHewer was the last full-scale pinball manufacturer left, and in the face of careening sales figures, they played their last gambit, the Holopin.

These new tables featured no holograms, but the pepper’s ghost illusion that reflected an actual screen across the playfield was a cool concept. The production costs for the new platform were extremely dear, as the tech required an entirely different size of table, thus necessitated upgrading the factory floor (at least, they figured, they were still getting money for upgrades.). The two games they made for the platform tested well, but even as they were put into production, whatever success they found wouldn’t stop the hatchet coming down from the boardrooms above.

In a story not terribly unique in the age of the corporate crucible, this hatchet was coming from inside of the house. BobsyHewer, from the start of its merger, had always been two halves of a company trying to make an awkward partnership work. The pinball division was mostly handled by the Hewer branch, nevermind which branding they decided to slap on which game, and Bally focused on an area in which they had long dabbled, developing the new kind of video slot machines that were starting to dominate the casino floors of Las Vegas. Soon they began to branch out into other premium markets, primarily up-scale health clubs – medium-effort, high-profit scams – once the pure undistilled carnyism of Vegas had fully infected them.

By 1999, Bobsy was a money-flush rising star in the coming merger games, while Hewer had become a sentimental money-sink. In reality, the Holopin project had only been OKed as a sop to the division, a way to disrupt their production line and keep them busy, with their energies focused elsewhere as the contract of death was carefully collected and collated, the burial already planned and paid for.

On August 9th, 2000, shortly after producing the first run of Holopins, Hewer was suddenly shuttered. Employees were escorted from the building. Bobsy had won its near century-long war with Hewer by swallowing them, and then murdering both the company and pinball in a single stab. Well played, you incredible capitalist pieces of pig shit… well played.

But, as the most piece-of-shit racist writer in history has said: over strange eons, even death may die. And sometimes a good death or two is necessary to revitalize any form of art. There were still a few small-time pinball shops out there, and there was still an audience; an aging but die-hard target market determined not to let the whole pinball thing vanish into the sands of the antique kingdom of wretched Ozymandias… although they might not have put it quite like that.

The white men of Generation X were maturating into early middle age with too much money from too many high-paying white tech jobs, and they shared a collective lust for expensive toys to fill the spiralling maw of void and shadow inside of their hearts. What these pent-up, unhappily divorced white men wanted to do was FUCKIN ROCK! But, y’know, in a way they were entirely familiar with.

So came the rebirth of Pinball, so shortly after its death that one might dare to accuse me of poetic exaggeration. This was pinball marketed almost specifically to these Gen X fellows. By doing so, the industry began to thrive again – not as a big-time concern, but as a low-level scheme that could keep on running as long as these very big boys were alive and had money to throw in the trash. Pinstar’s small-time Chicago Street operation was suddenly the biggest kid on the block, and new boutique production shops with small teams started to pop up with the idea of maybe becoming the new number two, Prisoner-style.

First, one Rock pin came out every couple of years. Then the flood started. All those 70s and 80s rock properties that had been apparently dead for a decade roared back into this new strange eon (again, fuck that guy,) as the primary hobby of the average 40-year old white dude became choking down as much nostalgia as he could, in order to ease his pain from having to move constantly into a future he hated.

And since the idea of authenticity (a trick of capital, anyway) was dead in America (probably for the best), there was no real downside to making any old band into a game if there were enough of its fans with money to buy it. As long as they could turn a small profit off the previous lot, they could then immediately make another. It’s why there’s a Saliva pinball table, why there’s a pinball table dedicated to Blink-182, why there’s a recently released Winger game, which is almost entirely dedicated to making fun of Winger, but still “about” WInger in the technical sense.

And so this hall, so far away from the throbbing crowd at the Logic Gate’s front entrance, yet so buzzing with a swiftly tilting masculine energy, is loaded down mostly with fifteen years of nostalgia-bait, a decade and a half of games dedicated to established, mainstream rock bands, the kind of shit for people who try to buy back the heady days of their Iterations, back when music and pinball actually made them actually feel something.

It’s mostly newer machines that propagate the Rock Room, with the pins of the dot matrix era rapidly losing floorspace to the LCD-screen revolution of the last decade (pinball machines are basically just full-on PCs these days, with pinball bits attached like accessories.) These newer games have deep and complex rule-sets which you pretty much need a detailed flowchart to progress through. The high-def screens show clear video scenes rather than murky abstractions. There’s full Dolby Surround sound, backed up by decent speakers and a massive bass unit that thrums in time with the violent shaking that modern pins are capable of. They are ferocious pins that rock and shake and snarl.

Honestly, there’s a lot of games in this hallway that are pretty fun. I may be a pretentious partisan to a few specific eras, but I like playing every iteration of pinball there is, and I’m clearly a sucker for novelty like anyone else. On days when it’s less busy, and I’m all by my anonymous white boy self, I can spend some time here. But when it grows into a crowd, there’s a vibe shift that makes it an uneasy space.

As we carefully continue our traversal of the crowd, which numbers in the dozens by my quick head count, I note a few of my favorites amongst a bunch of trash I couldn’t care less about. In particular, I feel a slight Pull towards the Slipknot: the Subliminal Verses pin, because Slipknot is a fun little band (I won’t be taking any questions) and their nods to fascism are at least supposed to be tongue and cheek, (and also that album was recorded in a haunted fuckin’ house.)

I’m also drawn to the less tongue-and-cheek version of fascism a few games down: Pantera: A Vulgar Display of Pinball, (right now there’s a dude playing it who you can exactly imagine, I ain’t even gotta bother to describe him.) Pantera’s music isn’t something I’m going to listen to on my own time, but I have to admit, it’s catchy when presented in bite-sized pinball form, even though the game’s design only puts the thinnest veneer over what is, clearly, a celebration of violent neonazi rallies. Hey, the modes are super fun, what’cha gonna do? Ethical consumption, ‘n all ‘at!

And although the game’s so new and popular that the Logic Gate has yet to acquire an extra from the Carnival’s Grand Midway Plaisance, (or if they have it, it’s tucked away in the “Special Stash” (Holy Jesus Fucking Christ, these dipshits are lame,)) I’m very much looking forward to the new Slayer game, even though one of their most popular songs is a celebration of the life and acts of the “underground’s” favorite serial-killer Nazi sadist.

Y’know, there truly does seem to be a line that runs through a lot of these games, and through a lot of the other newer games in the Logic Gate. White media has gone pretty fashy in the last decade… I mean, more so than usual. And looking at it objectively, I’m a fan of some of the worst offenders.

I guess I like them… ironically? Nah… that’s a lousy excuse, because I know the first time I activate “RAINING BLOOD” mode on that machine, and that riff starts crunching through the speakers, and the game goes all black except for peels of red lightning crackling across the whole of the backglass and playfield… I know those chills and that rush won’t be ironic.

I may not, but pinball does deserve so much better than just this.

And so we beat on, bodies against the current of B.O. and sketchy masculine energy permeating the ambient ether. We do what we can to move past and through chirping groups of dudes who don’t precisely feel menacing, but who sure are happy to spread the fuck out in areas without a lot of space, or sometimes burst into horseplay that adds an unhappy musk of testosterone to the general ambiance of masculinity.

Sometimes, we do have to squeeze around these guys, as even the most apologetic “excuse mes” don’t penetrate their self-possessed haze. Picky and Etch, who are a little ahead of us, move much more gingerly and rapidly than me and the Kid. I understand their attempts to not touch any part of any fellow standing in our way, but I have to laugh a bit because it sort of looks like they’re doing the robot.

The Rock Room is only about 80 meters long, but it takes us several minutes to reach a small open area toward the entryway, where the older, classic pins are huddled. They are, sadly, the least played pins in the hall, owing to the fact that a huge chunk of folks outright refuse to play pinball tables that don’t feature the most modern kit, deigning to play on games with dot matrix screens only if they must, and demanding ramps and other now-expected accoutrements.

I thought a bit like this in my callow youth, so I can at least understand it… but it does make me a bit melancholy. Then again, this means that, anywhere in the Logic Gate’s GP areas, there’s almost always an open game that I love, waiting for me to play it. And that is quite all right with me.

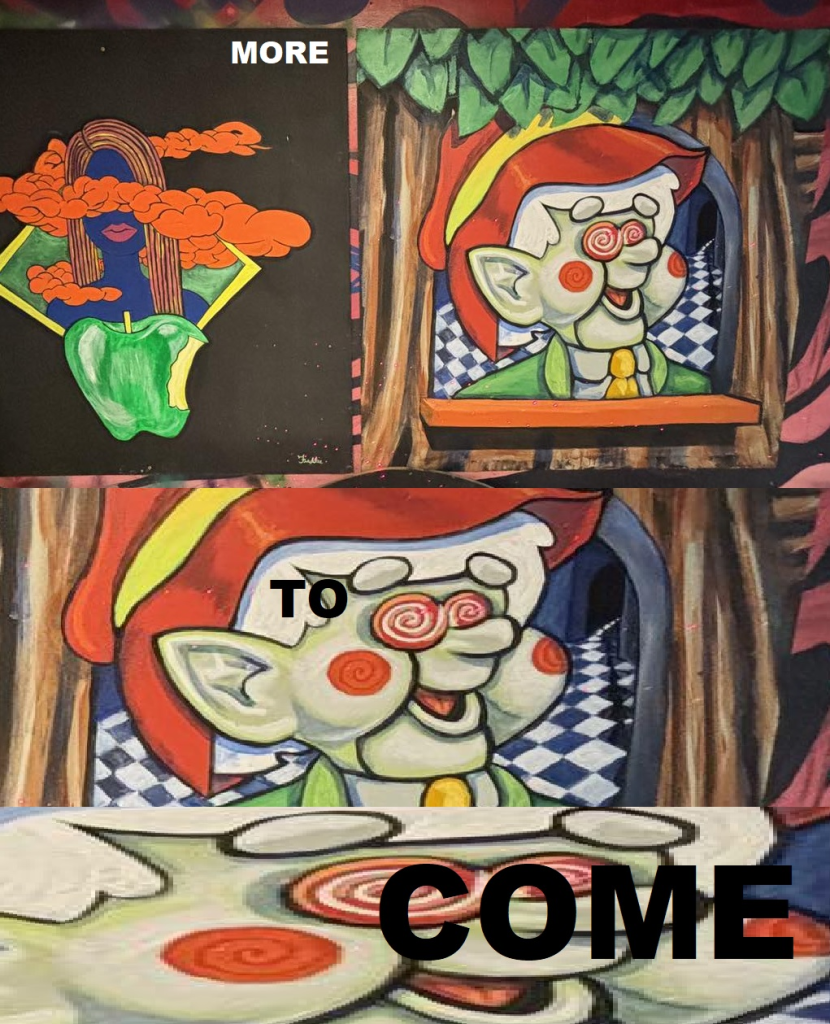

Picky slows her pace, and seems to decide we’re taking a break here, as she leans casually on a Cher! pin, her head lining up roughly in conjunction with Cher’s multi-colored face, done up in that beautiful, hideous late-70s aesthetic. They look a little like half-sisters, with one of them having been fathered by Henri Matisse on acid.

“Dickhead central never fails to disappoint.” she half-shouts, taking a languid stretch. We all form around and just sort of hover, as the noise is not conducive to conversation, particularly the rattle coming from the boisterous group of dudes who block our exit. They’re an ostentatious bunch, attempting to dress much older than their age, all white polos and khakis like it’s the fucking Northshore Suburbs or some shit.

This outfit is certainly a style of the day, but pretty often it turns out to be the style of budding fascists. Is this particular group of white men actually fascist? Well, yes, almost certainly, they’re a bunch of white boys, but do they know they are? Like if you called them out, would they take offense at the association, and if they did, would that supposed umbridge just be another fascist word game?

(Fascists, of course, love playing word games. If you get someone to play a word game with you, you can almost always change the rules to assure your rhetorical victory. To say fascists like to play word games is to say they like to win them.)

These cats congregate around the “Fresh Cuts” (sigh) section, right at the Rock Room’s entrance, which generally features six of the most popular pins in the hallway, three a side, all in their own little cluster. Often, these are doubles of machines that are also present further into the corridor, as those who dwell deep here are happy to share with the GP, as long as the GP stay the fuck away from them.

The older white men down the way materially support these kinds of young white men (if indeed they are those kinds of young men) in all sorts of ways, visible and invisible, from the thoughts they encourage to the spaces they provide, even putting a little money in to help fund the future RAHOWA once in a while. But they don’t really want to have to be around them, because young fascists are deeply creepy weirdos.

I take a glance over, just a glance, because I wouldn’t want to accidentally make any eye contact (eye contact with strangers does things to my weird brain that I do not like.) Somehow, although there are only five of them, they essentially consume the space of all six pins, even though they’re only playing on one.

They’re running a five-player game of The Dave Matthews Band pin, which isn’t exactly “new” at this point, but which has proven extremely popular, enough to earn its space at the very front of the Rock Room, and the very back. I study their clothes a little closer out using the power of peripheral vision, and get the sense that they do seem more high-end frat boy than Proudy. Two of them have those cable-knitted, sleeveless sweaters that only assholes trying to give off monied vibes have ever worn. At least one of the fellows is wearing long knee shorts, which I ultimately can’t decide makes the situation better or worse. Same with the backwards safehaven caps.

(I kinda like the DMB pin, to be honest. It doesn’t make me temporarily enjoy their music like the Pantera pin, but the gameplay is actually really fun, and it always makes me laugh when What Would You Say pops on, and then guffaw if it reaches any of Jon Popper’s dynamic mouth harp solos. (What do you want from me, taste? It’s a fun silly little game with a satisfying multiplier system that just happens to be designed with frat boys like these in mind.)

Their loud joy seems more sincere than dominating… It’s just so hard to tell at the moment. The air of palpable male rage toward women on the Drop is, as of late, profoundly fragrant and foul – the soul sweat of the lonely-hearted, bleeding out of every pore and into the black hole of reactionaryism, which focuses this poorly-directed hatred to fuel the self-organization of reactionary systems, such as incel onboarding and encouragement of racial hatred.

“Did you bring us to the Gate on open fascism night?” I finally offer, deciding to raise my voice over the din after it feels like we’ve been “resting” here a bit too long.

“Not on purpose!” Picky replies, with a wink. She takes a long, torpid look at the group, studying them as if they were a pack of animals. The shortest of them finally returns the apathetic stare with a glance that’s too short to interpret as either curiosity or challenge. Picky seems satisfied, and returns her attention to her busted cuticles. “They seem like normal DMB fans.”

“That doesn’t really answer the initial question,” I point out.

“Guess not, but it doesn’t really matter,” Picky sighs. “We’re just here popping a squat and then moving on, maybe giving the boys a chance to make way before we have to push through any more flesh. …You’re doing your paranoia thing again, making up scenarios in your head that do not exist here in really-real life.”

“God I fucking hate it when you say I’m paranoid. Or use the phrase “pop a squat.”

“These guys look like “what about the men” bros anyway,” Etch half-yells, typing furiously on their phone with a fresh intensity. “They still have lots of room to grow into their misogyny, they’re likely a few years away from “it’s the women’s and queers fault my life feels like garbage, and they should probably be destroyed, except for breeding purposes.”

“You have some intense visions of the future,” the Kid hollers.

“No, I actually understand the concept of dialectical materialism and also use it to develop likely outcomes based on prior data.” Etch actually turns and looks at the Kid while they say this, and although I mostly agree with their sentiment, I know the Kid’s gonna lash out in retaliation.

There’s just enough space of silence to think everything’s going to be fine. Inwardly I make the choice to take initiative, which I already know is going to work out about as well as it ever does, but – thankfully? – the Kid has finally processed a rebuttal.

“What about them, though?” he says, pointedly, at Etch. He’s still having to raise his voice but his tone and cadence have changed to that of a patrician asking tough questions to a rebellious youth. I sure do hate when he does this shit.

“What about who?” Etch replies, apparently in an accommodating mood for trollish instigation.

“The men. What about them?” the Kid says slowly, as if the question were a profound gotcha. “Are the men not worthy of consideration in this new, supposedly liberated framework of social justice?”

“Nope!” Etch replies.

“See, how can a man who’s looking to genuinely understand all of these new ideas coming into prominence do so, when they’re being gate-kept by such snide misandry?”

“The whole conceptual framework of “misandry” is fucking bullshit, it’s a concoction of patriarchy to make a system of total oppression seem equalized!” Etch is now beginning to actually shout. Then their face sinks, and they seem to realize that they’ve gotten themselves into something they don’t want to be a part of. “Hey, is he really this disgusting or is he just doing a bit?”

“I mean, both, but this is a bit,” Picky hollers back. “It’s a real fun one, innit?”

“And you,” the Kid yelps, pointing towards Picky. “The worst of the bunch! Constantly putting down my masculinity in cruel and, frankly, ableist ways, using your position as the “big swinging dick” of Chicago Street to form your own matrices of hypnosis and thought-termination, calling these structures feminist when they’re very obviously constructed on frameworks of deference, respect, and power, a classic patriarchal dynamic!”

“Please shut up, the Kid!” Picky responds, and although her face remains neutral, her hollering is matching the Kid’s energy.

“No, I will not be silenced by the radical agenda of enemies of the state like you! Cultural Marxists and the radical feminist left that seeks to strangle all aspects of masculinity, good or bad, from the culture!”

Now the frat boys are starting to pay attention in our general direction. It’s actually unclear if they can hear any of the nonsense the Kid is spouting, but even if they can’t, it might appear to them that something interesting is happening over here (although there sure isn’t.)

The men (they are now all very much men, straightened spines, tense limbs and thinned eyes) stare at us now, as if trying to figure out if there’s anything they can do to use us as entertainment. The game they’re now ignoring loudly calls out PEOPLE IN EVERY DIRECTION! I would laugh if I wasn’t transfixed by their stares … their eyes are more intense, more challenging. I begin to build up a true sense of anger… but as black bile begins to swell in my humours, Picky grabs my arm and turns me towards her.

“Let’s not get ahead of ourselves, chief,” she says, giving me another quick wink. ““We have so many actual fish to fry tonight.”

“You’r in a real winking mode tonight,” I say, letting out a long, slow breath. I’m back in the real world, where engaging angrily with a bunch of big dudes is a genuinely dangerous and silly idea, especially with all of us being mostly armed and all. Thankfully, in situations of murky status between white groups, Bullet Lust rarely activates. But the thirst for competition, for combat, for beating the shit out of those weaker than you, that Pull definitely always lingers, for some, in the Junk Arcade.

Look, I’m not a brave guy. One time an old flame didn’t want to say I was a coward, so she called me “risk-averse” (Yeah, that’s the source of the bit.) I’ve never been called a coward more precisely or directly; it’s a moment where the external truly pinned me to the wall. It’s something I can’t and don’t want to forget, a part of who I am.

Anyway, both terms fit me comfortably, but inside of that pallid yellow streak running down my back, there’s a sort of white hot sliver of psychosis winding itself through that fearful line, a sick fetish for “justice” that sometimes overcomes my cowardice and gets me into real trouble. It generally comes on when I feel like men are sincerely threatening me or my pals, particularly if my pals I’m with at the moment aren’t other men. As Picky points out, this impulse is essentially patrician in and of itself, its supposed nobility emulating the ultimate objective of chivalry a bit too neatly. Sometimes she also adds that it’s one of her favorite things about me, which is nice I guess.

“Aww, c’mon, let him “protect our honor”,” Etch says, back in form. “It’d be funny to watch him get whaled on it by a bunch of awkward dipshits for a minute.”

“He can’t help it,” Picky says, looking at me with comically sad eyes. “He thinks he’s addicted to pinball but his real addiction is playing Lancelot and saving maidens. It’s so sweet and pathetic.” I decide I’m not going to respond or even move until someone does something at all useful. Out of my eye’s corner I can see the boys (they are boys again, slumped and goofy) attention slowly returning to the game, as our waning foolishness has been overwhelmed by their current need to play.

Look, we’re all addicts here. The Drop’s nickname isn’t metaphorical. The Junk Arcade is as valid an authentic expression of our state of psychological reality as the actual name of the Drop is, to both its literal material description, and also the thing it might do, at any moment, into the maw of nothingness below.

One might argue that calling the average citizen of the Drop a ”junkie” is trivializing the actual extent of an opioid or heroin addict’s need, but as the vast misuse of these medicines and their counterparts finds itself in every class and culture that make up the people of the Drop, it’s hard to deny we’re not all, on some level, clinically predisposed to addiction. And in the face of the Junk Arcade’s fraying, predatory medical industry, the distinctions between what counts as “addiction”’ continue to blur.

Trouble is, although we understand the chemical mechanisms of street drugs very well, we don’t know why we’re actually physically addicted to games. According to the science, There’s no goddamn reason for it to happen, as there’s no triggering mechanism apparent anywhere in our chemistry.

In many ways we still have a primitive understanding of what a “brain” even is, so there should be no surprise it contains a wealth of mysteries. But reactions this strong should easily register in either chemical testing or on a brain scan, like every other drug or moment of euphoric release. But they don’t. The pleasure of actually playing the game produces stronger-than-normal reactions that register clearly, but the actual Pull is invisible on every level that we currently understand. As far as we know at this point, it’s magic.

But despite the extreme vagaries of the mechanism, the actual symptoms of the Pull are very real, and very consequential. We’re addicted to the point that it gets in the way of everyday life, sometimes drastically so. We’re addicted to the point where we’ll occasionally have to traverse long distances and overcome challenging circumstances due to the specific Pull of a favorite machine. We’re addicted to the point where, say, just hypothetically, we’re being chased by dangerous people and suddenly have a nearly irresistible desire to stop cold and play a game of Air GripE II+.

So, there’s no “reason”. And yet, it is manifestly so, and has stood up to falsifiability in rigorous human testing (a decade long nightmare that we won’t delve into here.) And when it comes to magic, those of us on the Drop who believe in Mass Memory Manipulation and the idea of a “sufficiently advanced technology” at play don’t have much trouble accepting it as empirical science.